What Is a Review Hearing for a Mental Patient

A Phonak position statement most why hearing healthcare is vital for salubrious living

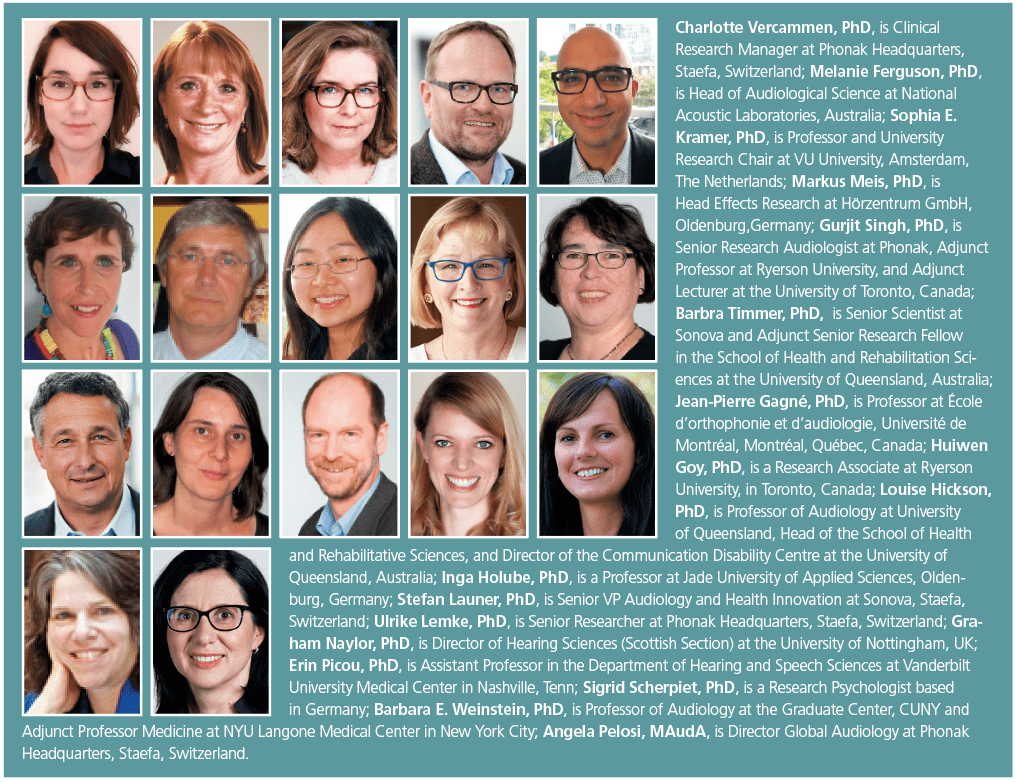

By Charlotte Vercammen, PhD; Melanie Ferguson, PhD; Sophia Due east. Kramer, PhD; Markus Meis, PhD; Gurjit Singh, PhD; Barbra Timmer, PhD; Jean-Pierre Gagné, PhD; Huiwen Goy, PhD; Louise Hickson, PhD; Inga Holube, PhD; Stef Launer, PhD; Ulrike Lemke, PhD; Graham Naylor, PhD; Erin Picou, PhD; Sigrid Scherpiet, PhD; Barbara Weinstein, PhD; Angela Pelosi, MAuDA

The goal of this position argument is to propose a model of well-being that would be easy to utilise in clinical audiology practice and considers the domains of socio-emotional, cognitive, and physical well-being as core dimensions of well-beingness. While hearing loss and its associated communication challenges tin can indeed bear on these cadre well-being dimensions, growing prove shows that hearing rehabilitation can provide benefits in the same three domains.

Editor'southward notation: In November 2019, Phonak convened a group of researchers and experts to discuss well-being. How can we ascertain well-beingness, peculiarly in a hearing wellness care context? Can we formulate enquiry directions to guide future piece of work, aimed at improving quality of life of people with hearing loss? This paper is a beginning reflection of this work. "Well-hearing is Well-Existence™" is a trademark of Phonak.

Hearing loss extends beyond hearing sensitivity, in many ways. The complication of hearing loss relates to the complexity of life. Meetings, eatery visits, family parties, etc, are all often set in noisy or reverberant surroundings. To agree conversations in these challenging situations, it is generally recognized that listeners rely on peripheral hearing sensitivity (reflected past a pure-tone audiogram), cardinal temporal sensitivity (the accurateness and efficiency by which auditory information is encoded, processed, and integrated throughout the auditory pathway), and cognitive skills.1,2 When bottom-up betoken processing degrades, such as through hearing loss, meridian-downwardly cognitive processing becomes more of import.3

The complexity of hearing loss also relates to its impact. Hearing is in many ways a social sense, and hearing loss can have a fundamental bear upon on communicating with others, and connecting to them. Hearing is likewise an emotional sense, and hearing loss can alter how we enjoy social gatherings, theater, music, and how we perceive emotions. Hearing loss can also bear on the ability to monitor changes in the acoustical environs, potentially impacting a sense of condom or security.

In other words, hearing loss can accept an impact on what we intuitively would refer to every bit "well-being." But can we put a definition on well-existence, with an accent on well-beingness in a hearing healthcare context?

Defining Well-existence

Well-being is a very personal and multi-dimensional concept.4 Information technology seems to inherently chronicle to things we value in life. For one person information technology tin be happiness, independence, or staying active. For another person it can be social participation, satisfying relationships with family unit and friends, or achievements in the workplace. One'south definition of well-existence is likely to be fluid and tin change throughout life. At times when we are confronted with physical wellness problems, physical well-existence can have on a more prominent part. At times whe we are in expert physical shape, other aspects of well-being may be more than of import.

The aim of this newspaper is to advise a model of well-beingness that would be piece of cake to use in clinical audiology do. In this model, we consider socio-emotional, cognitive, and concrete well-being as cadre dimensions of well-being. These three core dimensions are founded on the World Wellness System (WHO)'south constitution, which since 1948 describes health as "a country of consummate physical, mental, and social well-beingness and not merely the absence of illness or infirmity." 5 The definition hasn't changed since 1948.6 In 1986, the Ottawa Lease for Health Promotion did add together that "To reach a country of complete physical, mental and social well-beingness, an individual or group must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to modify or cope with the environment…Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, too every bit physical capacities."7

While hearing loss and its associated communication challenges tin can indeed impact these core well-being dimensions, growing evidence shows that hearing rehabilitation can provide benefits in the same three domains. This will be farther discussed in the post-obit sections of this newspaper. By also identifying enquiry directions and applications for clinical do, we want to farther explore these associations and encourage hearing care professionals to discuss the multi-dimensionality of hearing loss and well-being in audiological care.

Socio-emotional Well-being

Human beings are social creatures. Above many things, we value connectedness. For good reason, it seems. Increasing evidence demonstrates that having supportive social ties is associated with better health outcomes, such equally longer life expectancy,8 better physical,9,x and better mental health.eleven One of the longest longitudinal studies ever conducted even suggests that cerebral and emotional wellness in tardily-life may exist mediated by successful relationships—with significant others, at work, or in a community—around midlife.12

If social connectedness is proficient for the encephalon and the body, how do hearing and hearing rehabilitation fit in? One of the growing concerns related to hearing loss is the association with a smaller social network,xiii,fourteen feelings of loneliness,15-18 restricted interpersonal communication behavior,nineteen and an impact on the perceived quality of relationships with others.17,20,21 What if this socio-emotional burden associated with hearing loss acts as a mediating factor, negatively impacting long-term health outcomes? What if treating hearing loss could turn the situation around and allow us to live longer and healthier?

To appointment, in that location are no clear answers to these questions. One longitudinal written report showed that a sample of hearing assist adopters and not-adopters spent equal amounts of time engaged in solitary activities, such as watching Television receiver or reading.22 These results propose that hearing aids may not benefit social engagement. However, in the same report, individuals with hearing loss reported a lower perceived socio-emotional touch on of hearing loss while wearing hearing aids.22

The difference between actual (objective) and perceived (subjective) social impact or benefit may in fact be crucial. It has been suggested that feelings of social isolation or social engagement rather than objective measures may be predictive of health outcomes.23 While there is a need for further research on hearing aid employ, long-term health outcomes, and different measures of social engagement, the self-perceived social benefits of hearing aid employ seem evident to hearing aid adopters,24-26 and their communication partners.20,27

Indeed, more than and more research shows that involving communication partners in hearing rehabilitation is key. By applying such a family-centered intendance approach, the needs of all individuals involved in communication can be acknowledged and addressed.28,29 For persons with hearing loss, perceived social back up is linked to being successful and satisfied with hearing aids,30,31 but also to seeking assistance for hearing loss in the beginning identify.32-34 This is most probable due to the fact that communication partners, such as spouses, can experience difficulties because of the hearing loss of their partner as well—a miracle referred to as "3rd party disability."35,36

Additionally, people can deal with hearing loss in different ways, depending on personality traits, co-occurring life events, and social or ecology influences.37On the one paw, people may apply strategies to actively manage hearing loss, such as using hearing aids and/or advice strategies (engaged coping). On the other hand, people may avert addressing hearing loss, for example past denying or minimizing their hearing problems, withdrawing from social situations, or withdrawing inside social situations (disengaged coping),18 sometimes mediated past (self-)stigma.37,38 This may lead to social isolation and loneliness.

However, when persons with hearing loss and their communication partners apply aligned coping strategies (eg, by working together on dealing with and managing hearing loss), adjusting to hearing loss and hearing aids can be facilitated.20Audiologists and hearing care professionals can foster this alignment of coping strategies by providing information and support to both the person with hearing loss and his/her communication partners.

Cognitive Well-being

Cerebral well-being and healthy aging are hot topics for policy makers, researchers, and clinicians. Population aging is a fact. In many parts of the world, information technology is expected that ane-third of the population will be older than sixty years of age by 2050.39About a third of individuals in this age range will develop a hearing loss that interferes with daily life functioning.fortyAdding on to it, growing testify shows that persons with hearing loss are more at risk of developing clinically pregnant cognitive problems than their normal-hearing peers.41-44

At that place is no consensus yet on why hearing loss and cognitive pass up are associated. Recent data propose that it may exist a combination of different underlying mechanisms.45 One of those mechanisms could be a mutual crusade, affecting both hearing and cognition. Another mechanism postulates a short-term relationship between both, as a decline in hearing sensitivity requires compensatory cognitive resources that are then no longer available to perform other tasks. There is too the possibility of a long-term human relationship: sensory deprivation due to hearing loss may affect knowledge because of a prolonged period of reduced brain stimulation,45 or by interacting with other run a risk factors for developing cognitive problems, such as a smaller social network or depressive symptoms.46

Causal hypotheses imply that treating hearing loss —for example past amplifying the auditory signal through hearing aids— could have a positive upshot on cognition, protecting against or slowing down cognitive decline. To date, but a few longitudinal studies are available on this topic and they bear witness mixed results.47,48 Virtually one-half of the studies show a positive outcome of treating hearing loss, while the other half show no issue of hearing help utilise on long-term cognitive outcomes.47Randomized clinical trials on this topic are still ongoing49 and will shed more light on this field of study in the upcoming years. In the meantime, the promising emerging evidence that hearing aids may delay the onset of cognitive declinel-52 urges for the clinical recommendation to adopt hearing aids early on in the class of hearing loss.

Also, the immediate, brusk-term effects of hearing aids on cognition should not be underestimated. Wearing hearing aids during a listening chore permit listeners with hearing loss to practise meliorate on a secondary task (ie, a chore performed at the aforementioned time).53-56 Keeping in mind that a person's private cognitive capacity56,57or feel with hearing aids (eg, experienced versus first-time users57) may as well play a role, these dual-task studies suggest that making sounds more aural can brand listening less effortful. Reducing listening effort could costless up cognitive resource for purposes other than listening,58and could potentially as well reduce feelings of fatigue.59

As the generalizability of laboratory studies on listening try remain unclear, novel methods to measure hearing aid benefits in the field could provide more than insights. During Ecological Momentary Assessment, for instance, hearing assist wearers are asked to monitor their experiences in real-time. Past filling in a survey through an app, listeners can indicate how effortful listening is in different situations, or how they would rate their hearing performance, multiple times per day.60,61

Physical Well-existence

To navigate the world, we continuously endeavor to stay aware of our environs by integrating information that comes in through all the senses.62 Our sense of hearing, for example, contributes to a sense of environmental awareness: past processing and interpreting spatial information in sounds, listeners are able to monitor changes in the acoustical environment.63 Hearing loss can make this a lot more than challenging, equally it introduces difficulties to segregate and localize sound sources,64 simply also to detect subtle sounds, such every bit approaching footsteps or the splashing sounds from a wet and slippery flooring.

Therefore, it is likely that listeners with hearing loss spend more than attempt maintaining awareness of their surroundings than listeners with normal hearing. Similar to compensating for reduced speech communication intelligibility by "filling in the gaps," extra effort spent on auditory tasks like spatial awareness may compromise the availability of cerebral resource for other purposes.65 In an older more vulnerable population, it has been hypothesized that this could affect skills such equally postural control.66

Postural control is a complex motor skill that allows u.s. to achieve, maintain, and restore balance. It prevents us from falling down and allows u.s. to command our movements.67,68 To achieve postural control, we rely on a multisensory feedback system that integrates auditory,69 visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive information.70

More and more than research shows that older adults with hearing loss are significantly more at take chances of falling than their normal-hearing peers.66Every bit falls often result in detrimental outcomes—such as loss of confidence, serious injuries, or fifty-fifty mortality71-73—it is of loftier interest to identify and address risk factors for falling, such as hearing loss.

In addition to the cognitive effort hypothesis, information technology is known that postural control is particularly challenged when there is a vestibular problem. Given the close proximity of the vestibular and auditory systems, factors such equally infections or aging may impact both at the same time.66

Interestingly, some studies show positive effects of hearing aid use on postural stability and residuum in individuals with hearing loss.74-76 Other studies suggest that this may only be the case for persons with clinically significant vestibular problems.76,77Withal, well-fitted hearing aids tin can increase access to subtle sounds, fostering a listener's awareness of changes in the environment. Hearing-aids could thus increase feelings of safety or security, giving people the confidence to maintain an active and good for you lifestyle.

To date, all the same, almost no studies take investigated long-term concrete health outcomes post-obit hearing aid adoption. Holistic intervention programs aimed at improving the concrete and social wellbeing, likewise every bit the hearing and health-related quality of life in persons with hearing loss, are currently under investigation78,79and show promising pilot results.80

Potential Enquiry Directions, and Applications in Clinical Practice

The goal of this paper was to give a loftier-level overview of current scientific evidence linking hearing and hearing rehabilitation to the dissimilar dimensions of the "Well-Hearing is Well-Being" model. Of form, more work needs to be done, and at that place is a group investigating the relationship betwixt hearing loss and well-being to ascertain a conceptual model of well-being in those with hearing loss.4 Post-obit a inquiry priority consensus practice, we recommend future research to focus on how our hearing sense relates to dissimilar aspects of well-beingness, and how hearing rehabilitation might foster well-being. Also, we should explore collaborations with other disciplines to address hearing loss as a part of whole-person care, raising awareness and spreading knowledge on comorbidities in different healthcare fields, and advocating for hearing treatments equally part of interprofessional healthcare.

A close collaboration with full general practitioners, particularly, could foster preventative intendance, identifying and addressing hearing loss and its comorbidities earlier in fourth dimension.81Also, optimizing communication in healthcare settings82 and care homes83 deserves much more than attention, as optimal communication is invaluable for adequate history-taking, reducing the risk of misdiagnoses, fostering memory of information, supporting self-efficacy, and handling adherence.

Finally, hearing intendance providers are uniquely positioned to heighten awareness, and put hearing loss and hearing rehabilitation in a much broader context. Therefore, they can play a key function in changing the conversation from "needing a hearing aid because y'all do not hear well," to a chat about what hearing and hearing rehabilitation can truly mean for an individual in the broader context of healthy living. Through a family centered-care arroyo, discussing comorbidities, hearing engineering, and communication strategies, hearing intendance providers and hearing rehabilitation can be pivotal in fostering communication, participation in physically or cognitively stimulating activities, and social functioning—thereby serving as a catalyst for well-being.

References

1. National Enquiry Council. Speech understanding and aging. Working Group on Speech Understanding and Aging. Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics, and Biomechanics, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Didactics.J Acoust Soc Am.1988;83(3):859-895.

2. Pichora-Fuller MK. Cognitive aging and auditory information processing.Int J Audiol.2003;42(Suppl 2):2S26-32.

three. Pichora-Fuller MK, Kramer SE, Eckert MA, et al. Hearing damage and cerebral energy: The Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL).Ear Hear.2016;37(Suppl 1):5S-27S.

iv. Ferguson Yard, Ali Y. Understanding the relationship between hearing loss and mental wellbeing. Presented at: Hearing Well and Beingness Well—a Potent Scientific Connection; November 14-xvi, 2019; Frankfurt, Germany. https://world wide web.phonakpro.com/com/en/preparation-events/events/upcoming-events/hearing-well-and-being-well/program-hearing-well-and-being-well.html.

5. Earth Wellness Organization (WHO).Constitution of the World Health System. Geneva, Switzerland. 1947.

6. World Health Organization (WHO). Frequently asked questions. https://world wide web.who.int/well-nigh/who-nosotros-are/frequently-asked-questions.

7. World Health Organisation (WHO). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/. Published 1986.

viii. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review.PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.

9. Eisenberger NI, Cole SW. Social neuroscience and wellness: Neurophysiological mechanisms linking social ties with concrete health.Nat Neurosci.2012;xv:669-674.

10. Uchino BN. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes.J Behav Med.2006;29:377-387.

xi. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Tost H. Neural mechanisms of social risk for psychiatric disorders.Nat Neurosci. 2012;fifteen:663-668.

12. Malone JC, Liu SR, Vaillant GE, Rentz DM, Waldinger RJ. Midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development: Setting the phase for late-life cognitive and emotional wellness.Dev Psychol. 2016;52(3):496-508.

thirteen. Kramer SE, Kapteyn TS, Kuik DJ, Deeg DJH. The association of hearing damage and chronic diseases with psychosocial health status in older historic period.J Aging Health. 2002;fourteen(one):122-137.

14. Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The clan between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults.Otolaryngol – Head Cervix Surg (United states of america). 2014;150(3):378-384.

fifteen. Stam Yard, Smit J, Twisk JW, et al. Change in psychosocial health status over v Years in relation to adults' hearing ability in dissonance.Ear Hear.2016;37(six):680-689.

16. Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Negative consequences of hearing damage in old age.Gerontologist. 2000;twoscore(3):320-326.

17. Vas Five, Akeroyd MA, Hall DA. A data-driven synthesis of research evidence for domains of hearing loss, as reported by adults with hearing loss and their advice partners.Trends Hear.2017;21:one-25.

18. Heffernan E, Coulson NS, Henshaw H, Barry JG, Ferguson MA. Agreement the psychosocial experiences of adults with mild-moderate hearing loss: An application of Leventhal'south self-regulatory model.Int J Audiol. 2016;55:S3-S12.

19. Meis M, Krueger M, Gablenz PV, et al. Development and awarding of an notation procedure to assess the affect of hearing help amplification on interpersonal communication beliefs.Trends Hear.2018;22:i-17.

20. Barker AB, Leighton P, Ferguson MA. Coping together with hearing loss: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the psychosocial experiences of people with hearing loss and their communication partners.Int J Audiol. 2017;56(5):297-305.

21. Hétu R, Jones 50, Getty L. The impact of caused hearing impairment on intimate relationships: Implications for rehabilitation.Audiology.1993;32(6):363-381.

22. Dawes P, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, Klein BEK, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Hearing-assist use and long-term health outcomes: Hearing handicap, mental wellness, social engagement, cognitive office, physical health, and bloodshed.Int J Audiol.2015;54(xi):838-844.

23. Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJH, Beekman ATF, et al. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL).J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.2014;85(2):135-142.

24. Abrams HB, Kihm J. An Introduction to MarkeTrak Ix: A new baseline for the hearing aid market.Hearing Review. 2015;22(half-dozen):16.

25. Laureyns M, Best 50, Bisgaard N, Hougaard Due south. EHIMA. Getting our numbers correct on hearing loss, hearing care and hearing aid use in Europe. https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Getting-our-numbers-right-on-Hearing-Loss-and-Hearing-Care-26_09_16.pdf.

26. Ferguson MA, Kitterick PT, Chong LY, Edmondson-Jones M, Barker F, Hoare DJ. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2017;ix:CD012023.

27. Kamil RJ, Lin FR. The effects of hearing impairment in older adults on advice partners: A systematic review.J Am Acad Audiol.2015;26(2):155-182.

28. Singh G, Hickson L, English K, et al. Family unit-centered adult audiologic care: A Phonak position statement.Hearing Review. 2016;23(iv):16.

29. Meyer C, Scarinci N, Hickson L.Patient and Family-Centered Speech-Linguistic communication Pathology and Audiology.1st ed. New York, NY:Thieme;2019.

30. Singh G, Lau S-T, Pichora-Fuller MK. Social back up predicts hearing assist satisfaction.Ear Hear.2015;36(vi):664-676.

31. Hickson L, Meyer C, Lovelock K, Lampert 1000, Khan A. Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults.Int J Audiol.2014;53(Suppl ane):S18-S27.

32. Meyer C, Hickson L, Lovelock K, Lampert M, Khan A. An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults.Int J Audiol.2014;53(Suppl 1):S3-S17.

33. Pronk One thousand, Deeg DJH, Versfeld NJ, Heymans MW, Naylor Grand, Kramer SE. Predictors of entering a hearing aid evaluation period: A prospective study in older hearing-assist seekers.Trends Hear. 2017;21:1-twenty.

34. Meister, Grugel 50, Meis Chiliad. Intention to apply hearing aids: A survey based on the theory of planned beliefs. Patient Adopt Adherence. 2014;8:1265-1275.

35. Scarinci Northward, Worrall L, Hickson 50. Factors associated with tertiary-party inability in spouses of older people with hearing impairment.Ear Hear.2012;33(half dozen):698-708.

36. Scarinci Northward, Worrall L, Hickson L. The event of hearing harm in older people on the spouse: Development and psychometric testing of The Significant Other Scale for Hearing Disability (SOS-HEAR).Int J Audiol. 2009;48(10):671-683.

37. Southall K, Gagné J-P, Jennings MB. Stigma: A negative and a positive influence on help-seeking for adults with acquired hearing loss.Int J Audiol.2010;49(xi):804-814.

38. Gagné J-P, Jennings MB, Southall K. Understanding the stigma associated with hearing loss in older adults. Paper Presented at: Adult Conference: The Challenge of Aging; November 16-18, 2009; Chicago, Illinois. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7f35/f5d1a0ce78750cac20dcb5b90b3673ed9f66.pdf.

39. World Wellness Arrangement (WHO). World written report on ageing and health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7CA2BB888E8C8D28D28265D57B3B407C?sequence=1. Published September 30, 2015.

twoscore. Earth Health Organization (WHO). Global estimates on prevalence of hearing loss. https://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/estimates/en/.

41. Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Meillon C, Rullier Fifty, Dartigues J-F. Death, depression, disability, and dementia associated with self-reported hearing problems: A 25-year study.J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci.2018;73(10):1383-1389.

42. Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive part, cognitive impairment, and dementia.JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg.2018;144(2):115-126.

43. Deal JA, Betz J, Yaffe One thousand, et al. Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive turn down in older adults: The health ABC study.J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(5):703-709.

44. Osler M, Christensen GT, Mortensen EL, Christensen Yard, Garde E, Rozing MP. Hearing loss, cognitive ability, and dementia in men historic period nineteen–78 years.Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:125-130.

45. Pronk Thousand, Lissenberg-Witte BI, van der Aa HPA, et al. Longitudinal relationships between decline in voice communication-in-dissonance recognition ability and cognitive functioning: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam.J Speech, Lang Hear Res. 2019;62(4S):1167-1187.

46. Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Giulioli C, Meillon C, Rullier L, Dartigues J-F. Cocky-reported hearing loss, hearing aids, and cerebral refuse in elderly adults: A 25-year written report.J Am Geriatr Soc.2015;63(10):2099-2104.

47. Dawes P. Hearing interventions to prevent dementia.HNO. 2019;67:165-171.

48. Kalluri S, Humes LE. Hearing technology and knowledge.Am J Audiol.2012;21(2):338-343.

49. Bargain JA, Albert MS, Arnold K, et al. A randomized feasibility pilot trial of hearing treatment for reducing cognitive decline: Results from the Crumbling and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot Study.Alzheimer'southward Dement Transl Res Clin Interv.2017;iii(3):410-415.

50. Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, Tampubolon G, Pendleton N. Longitudinal relationship between hearing assist use and cognitive function in older Americans.J Am Geriatr Soc.2018;66(6):1130-1136.

51. Mahmoudi E, Basu T, Langa K, et al. Can hearing aids filibuster time to diagnosis of dementia, depression, or falls in older adults?J Am Geriatr Soc.2019;67(11):2362-2369.

52. Sarant J, Harris D, Busby P, et al. The effect of hearing aid use on cognition in older adults: Tin nosotros filibuster pass up or even ameliorate cognitive function?J Clin Med. 2020;9(1),254.

53. Downs DW. Effects of hearing aid employ on spoken language bigotry and listening effort.J Speech Hear Disord. 1982;47(2):189-193.

54. Gatehouse S, Gordon J. Response times to speech communication stimuli as measures of benefit from amplification.Br J Audiol.1990;24(i):63-68.

55. Hornsby BWY. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands.Ear Hear.2013;34(v):523-534.

56. Picou EM, Ricketts TA, Hornsby BWY. How hearing aids, background noise, and visual cues influence objective listening endeavor.Ear Hear.2013;34(v):e52-e64.

57. Ng EHN, Rudner Grand, Lunner T, Pedersen MS, Rönnberg J. Effects of noise and working memory capacity on retention processing of speech for hearing-assistance users.Int J Audiol.2013;52(seven):433-441.

58. Pichora-Fuller MK, Singh Chiliad. Effects of age on auditory and cognitive processing: Implications for hearing aid plumbing fixtures and audiologic rehabilitation.Trends Amplif.2006;ten(1):29-59.

59. Holman JA, Drummond A, Hughes SE, Naylor G. Hearing harm and daily-life fatigue: a qualitative written report.Int J Audiol. 2019;58(7):408-416.

60. Timmer BHB, Hickson 50, Launer S. Ecological momentary assessment: Feasibility, construct validity, and time to come applications.Am J Audiol.2017;26(3S):436-442.

61. Timmer BHB, Hickson 50, Launer S. Do hearing aids address real-world hearing difficulties for adults with mild hearing impairment? Results from a pilot study using ecological momentary cess.Trends Hear.2018;22:1-xv..

62. Campos JL, Bülthoff HH. Multimodal integration during cocky-motion in virtual reality. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT, eds.The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis;2012:603-628.

63. Brungart DS, Cohen J, Cord M, Zion D, Kalluri S. Assessment of auditory spatial awareness in complex listening environments.J Acoust Soc Am. 2014;136:1808.

64. Dobreva MS, O'Neill WE, Paige GD. Influence of aging on human sound localization.J Neurophysiol.2011;105:2471-2486.

65. Edwards B. A model of auditory-cognitive processing and relevance to clinical applicability.Ear Hear.2016;37(Suppl 1):85S-91S.

66. Jiam NT-L, Li C, Agrawal Y. Hearing loss and falls: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Laryngoscope.2016;126(11):2587-2596.

67. Horak FB, Macpherson JM. Postural orientation and equilibrium. In: Rowell LB, Shepherd JT, eds.Handbook of Physiology: Section 12, Exercise Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: American Physiological Lodge/Oxford Academy Press; 1996:255-292.

68. Horak FB. Postural orientation and equilibrium: What exercise we need to know about neural control of remainder to foreclose falls?Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii7-ii11.

69. Gandemer 50, Parseihian M, Kronland-Martinet R, Bourdin C. Spatial cues provided by sound improve postural stabilization: Prove of a spatial auditory map?Front Neurosci.2017;11:357.

70. Peterka RJ. Sensorimotor integration in human postural command.J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1097-1118.

71. Parkkari J, Kannus P, Palvanen M, et al. Bulk of hip fractures occur as a result of a fall and impact on the greater trochanter of the femur: A prospective controlled hip fracture written report with 206 consecutive patients.Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:183-187.

72. Kannus P, Parkkari J, Koskinen S, et al. Fall-induced injuries and deaths among older adults.JAMA.1999;281(20):1895-1899.

73. Colina K, Schwarz J, Flicker L, Carroll S. Falls amongst good for you, customs-home, older women: A prospective report of frequency, circumstances, consequences and prediction accurateness.Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23(1):41-48.

74. Negahban H, Cheshmeh Ali MB, Nassadj G. Result of hearing aids on static residual function in elderly with hearing loss.Gait Posture. 2017;58:126-129.

75. Rumalla K, Karim AM, Hullar TE. The outcome of hearing aids on postural stability.Laryngoscope.2015;125(3):720-723.

76. Vitkovic J, Le C, Lee South-Fifty, Clark RA. The contribution of hearing and hearing loss to residuum control.Audiol Neurotol.2016;21(4):195-202.

77. Maheu M, Behtani L, Nooristani Yard, et al. Vestibular part modulates the benefit of hearing aids in people with hearing loss during static postural control.Ear Hear. 2019;40(half dozen):1418-1424.

78. Jutras M, Lambert J, Hwang J, et al. Targeting the psychosocial and functional fitness challenges of older adults with hearing loss: A participatory approach to accommodation of the walk and talk for your life program. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(7):519-528.

79. Lambert J, Ghadry-Tavi R, Knuff K, et al. Targeting functional fitness, hearing and health-related quality of life in older adults with hearing loss: Walk, Talk 'northward' Listen, report protocol for a airplane pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;eighteen(47):1-12.

80. Jones CA, Siever J, Knuff Grand, et al. Walk, talk and listen: A airplane pilot randomised controlled trial targeting functional fitness and loneliness in older adults with hearing loss.BMJ Open. 2019;ix(4):e026169.

81.Weinstein BE. Screening for otologic functional impairments in the elderly: Whose job is it anyway?Audiol Res.2011;1:e12.

82. Mick P, Foley DM, Lin FR. Hearing loss is associated with poorer ratings of patient-physician communication and healthcare quality.J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2207-2209.

83. Crosbie B, Ferguson M, Wong M, Walker D-Grand, Vanhegan South, Dening T. Giving permission to care for people with dementia in residential homes: Learning from a realist synthesis of hearing-related advice.BMC Med. 2019;17(54).

Correspondence can be addressed to Hour or Dr Vercammen at: [e-mail protected]

Citation for this commodity: Vercammen C, Ferguson M, Kramer SE, et al. Well-hearing is well-existence. Hearing Review. 2020;27(3):18-22.

Epitome: Syda Productions | Dreamstime.com

Source: https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/patient-care/counseling-education/well-hearing-is-well-being